RSA encryption is one of the fundamental building blocks of modern digital security. It underpins everything from secure websites to encrypted emails and VPNs, making safe online communication possible.

This article breaks down what RSA encryption is, how it works, and why it’s essential.

TL;DR

RSA is an asymmetric encryption algorithm that uses a public key to encrypt data and a private key to decrypt it.

It relies on the difficulty of factoring very large numbers generated from two secret prime numbers.

RSA is used for both encryption (confidentiality) and digital signatures (authenticity and integrity).

In practice, RSA usually encrypts a symmetric key (like an AES key), which then encrypts the actual data.

Modern deployments should use at least 2048‑bit RSA keys and secure padding schemes (e.g. OAEP, PSS).

RSA underpins HTTPS, secure email, VPNs and signed software updates across the internet.

It is computationally heavy compared with symmetric algorithms, so it is not used for bulk data encryption.

Quantum computing poses a long‑term threat to RSA, driving interest in elliptic curve and post‑quantum cryptography.

What is RSA encryption?

RSA (Rivest–Shamir–Adleman) is an asymmetric encryption algorithm that uses a pair of mathematically related keys: a public key and a private key. Unlike symmetric encryption, where the same key encrypts and decrypts data, RSA uses one key to encrypt and a different, linked key to decrypt.

In practice, the public key can be shared openly and is used to encrypt data or verify digital signatures. The private key must be kept secret and is used to decrypt data or create digital signatures. This split between public and private keys solves a long‑standing problem in cryptography: how to share a key securely over an insecure channel like the internet.

The basic idea behind RSA

At the heart of RSA is a mathematical “one‑way” function. It is easy to multiply two large prime numbers together, but extremely hard (with current computing capabilities) to take the result and work out which primes were multiplied.

RSA relies on this property of prime factorisation. A public key is built from a large number that is the product of two primes; the private key is derived using those primes. Anyone can see the public number, but without knowing the original primes it is computationally infeasible to reconstruct the private key.

Public and private keys in more detail

An RSA key pair consists of three core values: a modulus, a public exponent, and a private exponent. The modulus is the product of two large primes and is common to both keys. The public exponent is used with the modulus to form the public key, and the private exponent with the modulus forms the private key.

Because of the way these values are generated, anything encrypted with the public key can only be decrypted with the matching private key, and vice versa. This relationship is what allows RSA to support both encryption (for confidentiality) and digital signatures (for authenticity and integrity).

How RSA key generation works

The key generation process follows a well‑defined series of mathematical steps:

Two large prime numbers are chosen at random. In real systems these primes are extremely large, typically hundreds of digits long.

These primes are multiplied together to produce the modulus. This number is made public and forms the core of the RSA key.

A function of the primes (often Euler’s totient or a related value) is calculated. This value is used to ensure the keys will work correctly.

A public exponent is chosen. This is usually a fixed number that makes calculations efficient while remaining secure.

A private exponent is calculated using the public exponent and the totient value, via modular arithmetic, so that the encryption and decryption operations become mathematical inverses.

The end result is a public key (modulus + public exponent) that can be shared freely, and a private key (modulus + private exponent) that must be protected. If an attacker cannot factor the modulus back into the original primes, they cannot feasibly derive the private exponent.

How RSA encryption works in practice

From a user’s perspective, RSA encryption is straightforward: the sender takes the recipient’s public key and uses it to encrypt data. Only the holder of the corresponding private key can decrypt that data.

Mathematically, the encryption process converts the plaintext into a number, raises that number to the power of the public exponent and then applies a modulus operation with the shared modulus. Decryption does the reverse using the private exponent. Although the underlying maths is intricate, modern libraries hide this complexity and provide simple “encrypt with public key, decrypt with private key” interfaces.

RSA and digital signatures

RSA is also used for digital signatures, which provide authenticity (proving who sent a message) and integrity (that it has not been altered). In this scenario, the roles of the keys are effectively reversed.

The sender uses their private key to sign a hash of the message. Anyone with access to the sender’s public key can verify that signature. If the signature is valid, it shows that the holder of the private key created it and that the message has not been changed since it was signed.

Typical RSA key sizes

The security of RSA depends heavily on key size. Key size is usually expressed in bits and represents the length of the modulus. Larger moduli are harder to factor, and so more secure.

Historically, 1024‑bit RSA keys were common, but are now considered weak against well‑resourced attackers. Today, 2048‑bit keys are generally regarded as the minimum for new deployments, with 3072‑bit and 4096‑bit keys used where longer‑term or higher‑assurance security is required. Larger keys increase security but also increase computational cost, particularly on constrained devices.

Where RSA is used in the real world

RSA appears in a wide range of protocols and systems that users interact with daily, often without realising:

Web security: RSA is widely used within TLS/SSL to help establish secure HTTPS connections between browsers and websites.

Email encryption: Tools such as S/MIME and PGP can use RSA for encrypting emails and for signing them.

VPNs and remote access: Many VPN implementations use RSA during the handshake phase to authenticate endpoints and exchange keys.

Software updates: Vendors frequently use RSA signatures to ensure that software updates are genuine and have not been tampered with.

In many of these cases, RSA is not used to encrypt large payloads directly. Instead, it protects a symmetric key (for example an AES key), which then encrypts the bulk data. This hybrid approach balances security with performance.

Strengths of RSA

RSA became a de‑facto standard in public‑key cryptography because it offers several compelling advantages:

Asymmetric design: The separation of public and private keys simplifies secure communication between parties who have never met.

Flexible functionality: The same algorithm supports both encryption and digital signatures.

Mature ecosystem: RSA has been studied for decades, and robust, well‑tested implementations exist in almost every major programming language and platform.

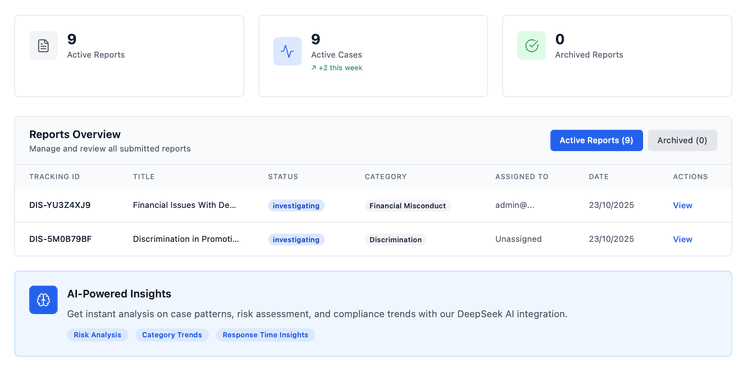

For organisations and products like Disclosurely, this maturity and interoperability make RSA a dependable building block within broader security architectures.

Limitations and vulnerabilities

Despite its strengths, RSA is not without weaknesses and constraints. Its security is based on the practical difficulty of factoring large integers. If a new algorithm or computing paradigm made large‑scale factoring efficient, RSA would become insecure. Quantum computing poses a theoretical threat here, as algorithms like Shor’s could, in principle, factor large numbers efficiently on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer.

RSA is also computationally heavier than modern symmetric algorithms. Directly encrypting large files or streams with RSA is inefficient, which is why it is usually reserved for small pieces of data, such as keys or hashes. In addition, RSA implementations must use proper padding schemes (such as OAEP for encryption and PSS for signatures). Poor padding or flawed random number generation can lead to practical attacks, even if the mathematics is sound.

RSA, compliance and secure reporting

For a compliance and whistleblowing platform such as Disclosurely, encryption is not just a technical requirement but a trust and regulatory issue. RSA helps address several key concerns:

Confidentiality: Reports and messages can be encrypted so that only authorised recipients, holding the correct private keys, can read them.

Authenticity and integrity: Digital signatures based on RSA can confirm that documents or notifications originated from the platform and have not been altered in transit.

Key separation: Different key pairs can be used for different roles or functions (for example, one for backend services, another for email signing), aligning with least‑privilege and segregation‑of‑duties principles.

Used alongside strong symmetric encryption and robust key management, RSA contributes to meeting legal and regulatory expectations around data protection and secure handling of sensitive disclosures.

RSA and modern alternatives

In recent years, there has been growing adoption of alternative public‑key algorithms, particularly elliptic curve cryptography (ECC). ECC can offer comparable security with much shorter key lengths and lower computational overhead, making it attractive for mobile and IoT environments.

However, RSA remains deeply embedded across infrastructure and standards. Many systems operate in mixed environments, supporting both RSA and ECC to balance interoperability with modern security best practice. Looking ahead, post‑quantum algorithms are being standardised to resist potential quantum attacks, but RSA will likely remain part of the cryptographic landscape for some time, especially in legacy and transitional contexts.

Key takeaways for decision‑makers

For security, compliance, or product teams evaluating cryptography, a few practical points stand out:

RSA is a proven, widely supported asymmetric algorithm that underpins encryption and digital signatures across the internet.

Modern deployments should use at least 2048‑bit keys, robust padding schemes, and high‑quality randomness, all via reputable cryptographic libraries.

RSA is best used as part of a hybrid approach: encrypting or authenticating keys, hashes, and small pieces of data, rather than entire data streams.

Planning for the future means considering how RSA fits alongside ECC and emerging post‑quantum algorithms within a flexible, upgradeable cryptographic strategy.

Understanding what RSA encryption is and how it works helps frame broader decisions about protecting sensitive information, building secure products, and maintaining the trust of users who rely on platforms like Disclosurely to handle their data safely.